This exhibition was organized by the Asian Art Museum.

One island; one sheet of cotton; one extraordinarily complicated technique. Hundreds of artists. A melting pot of cultures.

One island; one sheet of cotton; one extraordinarily complicated technique. Hundreds of artists. A melting pot of cultures.

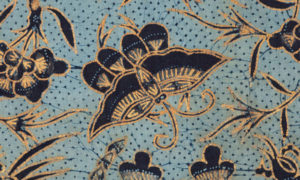

Few art forms have become as closely associated with a single location as the textile tradition of batik and Indonesia. Although the technique of patterning cloth through the application of wax is known in other parts of the world, in Indonesia, especially on the island of Java, this art form has reached the highest level of complexity.

Women in Java, working with simple materials, have developed remarkably diverse styles of decorating cloth. These styles are often associated with specific cities or villages and draw inspiration from a wide range of cultures and religions. This exhibition features batik made along the north coast of Java and the central court cities of Yogyakarta and Surakarta.

The island of Java has long been a crossroads for many cultures: from the early Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms of Central Java to the later Muslim sultanates; from communities of Chinese emigrants to pockets of colonial European residents. The textiles on view are the result of the meeting of these communities and the mingling of ideas, motifs, and symbols.

All of the works shown in the exhibition were selected from the collection of Joan and M. Glenn Vinson Jr.

Batiks were worn, and continue to be worn, by all types of people living in Java. They were also exported throughout the Indonesian archipelago and to neighboring countries in Southeast Asia.

Certain styles were favored by certain communities. For example, the Javanese of central Java preferred batiks using natural dyes with abstract repeated patterns and motifs derived from Hindu, Buddhist and Indian sources. For the Chinese community of the north coast, the color red and pastels of chemical dyes, motifs derived from Chinese sources, and floral patterns were more common.

Traditionally, clothing in Java tended to be made of square or rectangular lengths of cloth that were wrapped around the body. Sometimes these would be sewn into a tubular skirt or sarong, but long unsewn cloths were considered more formal. Both men and women wore the same type of lower garments. Men wore square head cloths that were folded turban-style. Women wore shoulder cloths and long thin textiles wrapped around their chests.

People wear batik less frequently now than in the past. Batik lower garments are still worn, both casually and on special occasions. Contemporary designers are also using batik in innovative ways to make clothing and other items for international audiences.

The word batik refers to a technique of creating patterns on a textile as well as to the textile itself.

Batiks were traditionally made by Javanese women in their homes. They were also made in the royal courts of central Java. At the end of the 1800s, European, Chinese, Arab and ethnically mixed Javanese began forming workshops that employed local women on the north coast of Java. In these workshops the owners, their spouses and their patrons may have been involved in the design of the textile, the women workers waxed the patterns by hand, and men stamped patterns and dyed the textiles.Today batiks continue to be made in small and large workshops across Java.

Designs are formed when hot wax is applied to a cloth, either with a small tool or a stamp of wood or copper. The textile is then immersed in a dye bath. The waxed portions of the cloth will remain undyed. For batiks with many colors, the textile has to be boiled or scraped free of wax, and then rewaxed to protect different sections of the cloth from each new color.

Most of the textiles in the exhibition were hand drawn, using a bamboo penlike tool, with a small copper receptacle for hot wax, and a thin spout or spouts from which the wax was poured onto the cloth. The wax was applied to both sides of the cloth before it is dyed.

Before the introduction of chemical dyes in late 1800s, women were highly regarded for their abilities to make natural dyes, and often kept their recipes secret. The process of dyeing a textile with natural dyes could be very time consuming. To obtain a deep blue, a textile might need to be immersed in an indigo bath as many as sixty times.

Textiles are often displayed by attaching the material to a panel using hidden pins or stitching. An alternative method of display is to use flexible strip magnets.

The magnets serve as gentle clamps, pressing the artwork against a padded sheet of steel hidden inside a backing board. Pressure can be adjusted by adding more magnets or more padding layers as needed, so that the artwork can be supported but need not be altered by pins, sewing, or other attachments. Since light-sensitive dyes and fibers are displayed only for short periods of time, these reusable mounts save time and money, too. In the exhibition Batik: Spectacular Textiles of Java, lengths of fabric appear to hang freely in cases along the walls. At the center of the gallery, flat skirt panels wrap around floating, three-dimensional forms. Curator Natasha Reichle intended the display to inform visitors how the textiles would look when in use. To achieve that goal, designer Marco Centin and conservator Denise Migdail worked together to develop dynamic mounts that still support the fine fabrics safely.

“The fine batiks being shown were too lightweight for Velcro® fasteners, and every stitch would have been visible as a pucker. Not to mention that after the display, every stitch would have to be clipped and removed!”

Denise Migdail, textile conservator, Asian Art Museum

Conservators always prefer to use the least invasive method to mount an art object for display. Where she could, Migdail took advantage of the flat, lightweight nature of batiks to use low-profile flexible magnets for support instead of pins. These thin, bendable ‘refrigerator’ magnets cannot support heavy weights, but the thin, flat weave of batiks are well suited for this style of mount.

This batik sash or shoulder cloth was unusually long: 122″ end to end. In order to fit the sash inside the display case, one end had to remain rolled. This configuration meant that the magnet strip would be placed on the front, where it would visible as a long, dark stripe across the top edge. In order to camouflage the bare magnet, the sash was photographed and the design printed out exactly to scale. The correct section of the printout was attached to the magnetic strip so that when installed, the print follows the pattern on the sash exactly. Under careful gallery lighting, the magnet is barely noticeable and the batik can be appreciated without distraction.

In addition to the magnetic strip mount shown above, the museum makes frequent use of rare earth magnet mounts for display. Because magnet mounts provide stable hanging mechanisms and can be custom designed to fit the size and weight of the art work, they are often useful on lightweight costumes, works on paper, and thangkas. You can find examples of magnet mounts throughout the museum in several different designs.

Heavy costumes often need overall support from a custom-made internal form, but magnets can still provide extra security and subtle adjustments. By securing magnets to a padded support inserted inside the shoulders of this Chinese Vest, the weight of the silk fabric could be evenly distributed without stitching.

Rare earth magnets are strong enough that they can be embedded in mat board and cut into narrow strips with mitred corners. When assembled, the strips look like a conventional window mat. Look for examples of these mounts in the Chinese Paintings Gallery (Gallery 15, Floor 3). In the Himalayan Gallery (Gallery 12, Floor 3), thangkas may have similar magnets hidden beneath the silk.

Daria Keynan, Julie Barten and Elizabeth Estabrook, “Installation methods for Robert Ryman’s wall-mounted works, The Paper Conservator Volume 31 (2007): 7-15.Gwen Spicer, “Defying Gravity with Magnetism” AICNews (Nov. 2010) vol. 35, 6:1,3-5.American Institute for Conservation Object Specialty Group Wiki, Magnet Mounts, (2011-12).

Main image: Lower garment (detail), approx. 1950, by Oey Soe Tjoen (1901–1975). Indonesia; Java. Cotton. Lent by Joan and M. Glenn Vinson, Jr.

This exhibition was organized by the Asian Art Museum.