Changing and Unchanging Things: Noguchi and Hasegawa in Postwar Japan considers the consequential friendship of two artists, one Japanese American but drawn to Japan, the other Japanese but influenced by the West, both in search of a new direction for modern art in the aftermath of the Second World War.

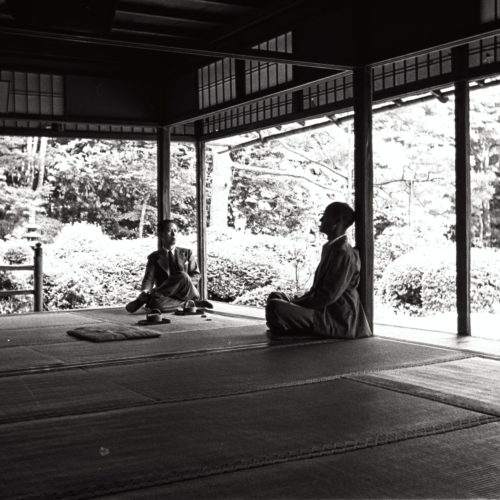

U.S.-born sculptor and designer Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) and Japanese painter, theorist and teacher Saburo Hasegawa (1906–1957) both reacted to the catastrophic effects of the war by questioning how art could balance tradition and modernity, Japanese culture and foreign influences, past and present. They were both committed to modernist practices, such as the removal of the inessential, truth to materials and a utopian belief of the power of art to improve society, but felt that modernism needed a new direction, one that could be provided by a deep exploration of Japanese art and design. Together, they visited historic gardens, palaces and temples around Kyoto to immerse themselves in traditional Japanese culture.

The exhibition traces the work, ideas and mutual influence of these two artists, one well known and the other little known outside Japan but who had strong ties to San Francisco. Focusing on work made in the decade following their meeting in 1950, the exhibition is organized around a series of themes that bring out the resonances between Noguchi’s sculptures and design work and Hasegawa’s explorations in painting, printmaking and photography. Situating the work of both artists side by side forcefully reveals their innovative fusion of Japanese tradition and modernist form and shared aesthetic sensibilities.

Around the time he met Noguchi, Hasegawa abandoned oil painting in favor of ink (sumi); he employed traditional materials and techniques to create abstract imagery. His work from the 1950s includes abstract calligraphy, rubbings, brush paintings, monotypes and block prints, and he often employed traditional formats such as folding screens and hanging scrolls.

Noguchi’s work was also profoundly impacted by his time in Japan with Hasegawa. For example, the iron, wood, and rope sculpture Calligraphics (1957) shows the influence of Hasegawa’s abstract calligraphy. The stele-like works Sesshu (the title is a nod to Hasegawa’s favorite ink-wash painter) and Orpheus (both 1958) are made of folded sheets of aluminum inspired by origami and kiragami.

Hasegawa spent the last years of his life in the United States, where he played a key role in transmitting Japanese philosophy and culture to the American avant-garde. After a year of professional successes in New York in 1954, Hasegawa moved to San Francisco to teach drawing and Asian art history at the California College of Arts and Crafts (now CCA) and lecture and teach the practice of tea ceremony at the now-defunct American Academy of Asian Studies. Hasegawa felt more appreciated in the U.S. than in his native Japan and believed that it was only in America that he could develop an abstract art rooted in Asian tenets.

Hasegawa’s death of cancer in 1957 at the age of 50 put a stop to that trajectory. It is fitting that San Francisco, the city where he left a strong legacy as a teacher and where his work was first exhibited (in 1952, at the Legion of Honor), is a venue for this first substantial consideration of Hasegawa’s work outside Japan.

The story of the friendship between Noguchi and Hasegawa and their shared artistic concerns adds nuance to the usual narrative of postwar art. Their practices do not fit neatly into any group, movement or style — in part because their profound interest in tradition was shared by few of their peers — but Noguchi’s and Hasegawa’s concern for balancing old and new, local and global, abstraction and representation seems as pressing, and complicated, today as it was in 1950.