This exhibition was organized by the Asian Art Museum in collaboration with Lawrence J. Ellison. Presentation at the Asian Art Museum is made possible with the generous support of Union Bank.

In the Moment: Japanese Art from the Larry Ellison Collection introduces 64 exceptional artworks spanning 1,100 years.

In the Moment: Japanese Art from the Larry Ellison Collection introduces 64 exceptional artworks spanning 1,100 years.

The exhibition explores the dynamic nature of art selection and display in traditional Japanese settings, where artworks are often temporarily presented in response to a Larry Ellison’s active involvement in displaying art in his Japanese-style home, shedding light on his appreciation for Japan’s art and culture.

Included in the exhibition are significant works by noted artists of the Momoyama (1573–1615) and Edo (1615–1868) periods along with other important examples of religious art, lacquer, woodwork, and metalwork. Highlights include a 13th–14th century wooden sculpture of Shotoku Taishi; six-panel folding screens dating to the 17th century by Kano Sansetsu; and 18th century paintings by acclaimed masters Maruyama Okyo and Ito Jakuchu.

“This exhibition offers a rare glimpse of an extraordinary collection,” said Jay Xu, director of the Asian Art Museum. “We aim to present it in a fresh and original way that explores traditional Japanese principles governing the relationship of art to our surroundings and social relationships.”

In Japan, an awareness of change — in season or occasion — is fundamental to the appreciation of art.

Temporary displays of art might last for a few moments or a few months before being replaced by another display to celebrate changing circumstances.

Each arrangement of art creates a unique viewing experience, altering one’s physical surroundings and relationship to the natural world and other people — a transient experience properly savored “in the moment.”

When the “moment” is over, the artwork is stored away. Due to the frequency of display changes, special handling and storage practices are followed to minimize damage to objects. Traditionally, Japanese sculpture and paintings not on view are rolled, folded or put in boxes and placed in storehouses called kura.

This exhibition will allow you to explore aspects of art selection and viewing in traditional Japanese settings.

Imagine standing in your storage room one day, surrounded by boxes of artwork. How would you go about choosing which artwork to display?

The factors often considered in selecting art in Japan include seasons, people, and occasions (celebrations, literary events, and other gatherings). In line with these traditions, we have chosen to rotate several pieces in the exhibition. We also want to share a piece that we were not able to include for display, a screen depicting two tigers and a leopard, in a web exclusive.

Seasonal art in Japan is exemplified by 17th-century folding screens depicting Waka poems over autumn grasses and morning glories with scattered fans. The screens, featured in In the Moment, include 16 fans tossed or blown into fields of plants associated with autumn. Scattered lines of calligraphy make the screens appropriate for a literary gathering.

The massive painting of the death of the Buddha is a great example of art used for specific occasions. It is removed from its box and unrolled for display one day each year on the anniversary of the historical Buddha’s death. Otherwise, the painting remains in storage.

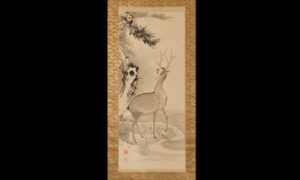

Auspicious paintings like Soga Shohaku’s cranes and deer might have been used for a celebratory occasion marking an age milestone.

The tastes, interests, and social relationships of the collector also factor into the selection of art for display.

Subject matter is a key variable: Larry Ellison favors paintings of flowers and animals and images of legendary battles and classic romances. His choice of paintings might focus on these themes with selections attuned to the interests and tastes of his visitors.

Art displays also reflect collectors’ stylistic preferences. Among the diverse painting styles seen in Japan, Ellison’s collection focuses on three major traditions.

Unlike oil paintings in the West, which sometimes stay on the wall for years at a time, many Japanese paintings are shown only for brief intervals — as little as a few hours or up to a few months — before being returned to storage, where they might spend most of their time. Traditional painting formats such as folding screens and hanging scrolls facilitate changing displays.

When looking at art, people familiar with this practice might pay attention to specific seasonal references and thematic links to occasion. For example, visitors might expect auspicious symbols for a birthday, and perhaps something more spiritual at a memorial service. Conversation at a social gathering or other event might begin by talking about the art on display.

For more than a thousand years, multi-panel folding screens such as scenes from The Tale of Genji provided temporary barriers for privacy and protection from wind, and served as easily changed decoration for ceremonial events and domestic living.

In Buddhist temples, painted scrolls were traditionally displayed with flower-filled vases, incense burners, candleholders, and other objects.

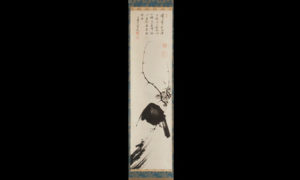

In a residential setting, painted scrolls like the mynah bird in a persimmon tree were often displayed in an alcove (tokonoma) with flowers and precious objects in other mediums, drawing attention to thematic and aesthetic relationships between disparate elements.

Other conditions of the environment, such as lighting and seating, also have an effect on how art is appreciated in Japan. Before the advent of electricity, natural light provided illumination for Japanese homes and had a profound, if subtle, effect on the appearance of artwork.

Depending on time of day and weather, painted screens might look quite different as light passes across gold-leaf surfaces and folded panels, cast in shadow; candles and oil lamps at night present yet another effect. And in traditional Japanese residences, guests sit on the floor at the same level as the artwork, offering an immersive perspective of painted scenery that changes as one moves about a room.

Larry Ellison’s collection focuses on three major traditions: works by members of the Kano school, Rinpa artists, and individual masters in 18th-century Kyoto.

Kano-school paintings, such as the screens showing auspicious pines, bamboo, plum, cranes, and turtles, are characterized by:

Characteristics of the Rinpa tradition are seen in the screens showing maize and cockscomb.

In many Rinpa paintings the following characteristics stand out:

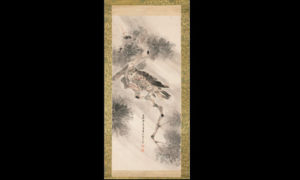

This group includes independent Kyoto-based artists who developed innovative modes of artistic expression between 1750 and 1800. One standout artist was Yosa Buson. His Kite in rain embodies an individualistic style, combining painting and poetry to render nature’s variety, using brushwork techniques of Chinese painting. Here, the kite is given great detail in contrast to the surrounding scenery, which is more impressionistic and atmospheric.

Main image: Waves and rocks, attrib. to Hasegawa Tōgaku (died 1623). Momoyama period (1573–1615) or early Edo period (1615–1868), 17th century. Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, light colors, and gold on paper. H. 70 x W. 1511/2 in. (each).

This exhibition was organized by the Asian Art Museum in collaboration with Lawrence J. Ellison. Presentation at the Asian Art Museum is made possible with the generous support of Union Bank.