Highlights from the collection illustrate how Japanese artists from the 15th to the early 17th century engaged with Chinese ink painting styles.

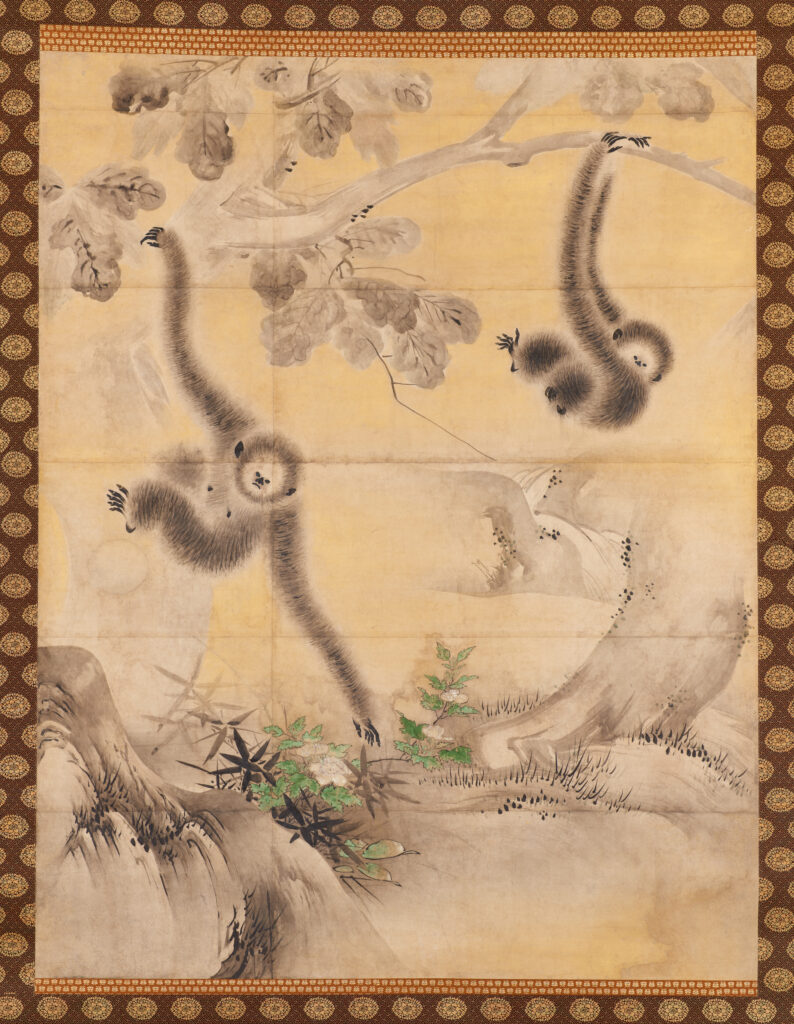

As Japan’s military leaders cultivated a taste for Chinese ink paintings during the Muromachi period (1333–1573), envoys and monks from China spread ink landscapes and figural subjects to Zen temples. By the late 1500s, tea masters like Sen no Rikyu (1592–1591) held Chinese ink paintings and calligraphy in high regard for display in tearoom alcoves. The superb works gathered in this gallery tell the story of how the taste for Chinese ink styles dynamically shaped Japanese painting from the 1400s to the early 1600s. Their themes and styles speak to the breadth of Chinese sources available to artists in Japan: a Zen parable, Catching the Ox, by the monk-painter Sekkyakushi (active approx. 1400–1450); expansive, Chinese-style landscapes by Shikibu Terutada (active 1500s); famous Chinese poets painted by Soami (1485–1525) and Unkoku Togan (1547–1618); and gibbons at play by Kaiho Yusho (1533–1615).

Top image: Landscape with the poets Tao Yuanming and Lin Hejing, one of a pair, approx. 1593–1605, by Unkoku Togan (Japanese, 1547–1618). Momoyama period (1573–1615). Ink and colors on paper. Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, The Avery Brundage Collection, B60D74+. Photograph © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.