The Timeless Tale

Bards and storytellers have been relating the Rama epic for over 2,000 years. Originating in ancient India, the story spread to Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand and beyond. The Rama epic now exists in dozens of languages and forms, and in as many religious and cultural contexts – from Hindu temples to village squares, from the Islamic courts of the Mughal emperors to the theaters of Buddhist Cambodia.

The earliest version of the tale is the seven-volume “Ramayana” said to have been composed by the poet Valmiki more than 2,000 years ago. Here’s a micro-summary:

The earth is threatened by powerful

demonic forces. To overcome them, the god

Vishnu takes human form and is born as

Prince Rama. When Rama is grown, court

intrigues force him into exile in the forest

with his wife Sita and his brother.

The king of demons, Ravana, kidnaps

Sita and holds her captive in his capital.

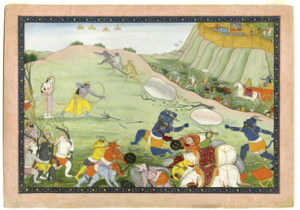

Rama allies with Hanuman and other

monkey warriors to conquer Ravana’s

forces and rescue Sita. After long and

bloody battles, Ravana is killed and Sita

and Rama are reunited.

Rama, however, expresses doubt that Sita

could have remained faithful to him and

rejects her. Sita insists on a test: she enters

a raging fire and emerges unharmed with

her integrity confirmed. Rama and Sita

return home, and Rama is crowned king.

For thousands of years, his realm enjoys

peace and prosperity.

Many tellings of the story end here, on this high note of triumph and reunification. But the sadder, more tangled continuation of the tale offers this alternate ending:

Sita’s virtue is again doubted, and Rama

sends her away. During her new exile,

she gives birth to their twin sons. Years later,

Rama summons her back to affirm her

purity once more. Unwilling to endure

further questioning, she calls on her mother

the earth to receive her and sinks out of

sight. Devastated, Rama rules for many

more years but finally returns to the

heavens and is reabsorbed into Vishnu.

Rama Today

As long as the mountains and rivers shall

endure upon the earth, so long will the story

of the Ramayana be told among men.

-Valmiki’s “Ramayana”

The Rama epic is not only alive and well today, it lives on in myriad mediums. The story and its characters continue to evolve in contemporary theater, dance, music, puppetry, movies, TV and even video games. Today Sita takes feisty form in works from Cambodian dance to graphic novels. Southeast Asian shadow puppet traditions persist. Gigantic effigies of Ravana are set aflame to cheers in North India as part of an annual festival theater, the Ramlila (literally, “Rama’s play”). In past decades, the epic poem has taken on political overtones as its characters have acquired nationalistic or regional significance. And in recent Bay Area history, an animated film interpretation featuring a buxom Sita and less-than-admirable Rama sparked controversy and protests.

The adaptations, interpretations and commentary are endless. What’s clear is that the Rama epic still thrives and maintains its import in artistic, religious, cultural and political spheres. Each retelling is a testament to the lasting power of the drama and its moral quandaries.